Cleantech

Carbon capture is all the rage. Can these startups make it profitable?

March 29, 2021 View comments (5)

A growing number of startups have ambitions to turn carbon dioxide emissions into cold hard cash—with the hope of charting a course to clean up emissions-heavy industries without relying on perpetual government subsidies.

Capturing carbon—whether it be from the air, ocean or factory smokestacks—has amassed prominent fans who see it as a moonshot that could one day help humanity reverse course on CO2 emissions.

Elon Musk recently volunteered $100 million of his own money as part of an XPrize competition to be doled out to carbon capture startups. Bill Gates has backed Carbon Engineering, a prominent startup that scrubs CO2 directly from the atmosphere. And BP, Shell and the Norwegian government have all launched significant projects to catch and bury carbon.

But the industry has received relatively little funding from venture capital in recent years, despite startup investors' frothy backing of electric vehicles and related technology.

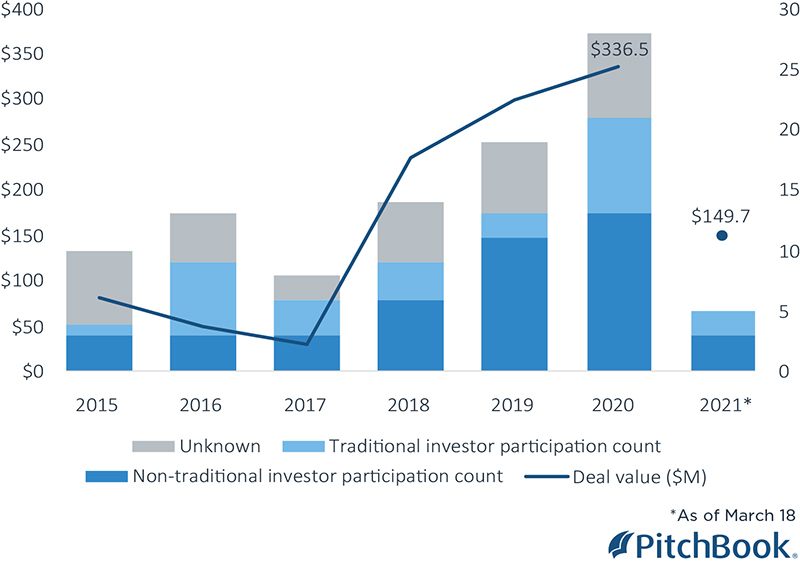

VC-backed carbon capture startups took in $336.5 million last year to set a modest record, according to PitchBook data. Much of that investment was driven by non-traditional investors—oil companies, governments and others—who participated in nearly two-thirds of all deals.

Carbon capture VC deals, global

Investors have plenty of reasons to be skeptical. Carbon-capture projects often involve immense capital investment, political uncertainty and vastly longer time horizons than typical startup efforts. And storing CO2 underground in and of itself isn't a business; it relies on subsidies or a carbon market with sufficiently high prices to function.

"You can capture the carbon, but then what do you do with it?" said Andrew Chung, founder and managing partner of 1955 Capital, a VC firm that invests in sustainable technologies. "You want to be able to reuse it."

Carbon Engineering and Climeworks are among the most prominent companies to attempt direct-air carbon capture at scale. The approach pulls in air using massive fans, sends it through a liquid or solid filter to remove the CO2, and typically stores the gas permanently underground.

Direct-air capture could effectively allow humanity to turn back the clock on past emissions, and it has gained traction with corporations and governments in recent years. Shopify recently became one of the largest corporate buyers of the technology in a deal with Carbon Engineering to capture and store 10,000 metric tons of CO2.

But such direct-air carbon capture systems remain far more expensive than natural solutions like planting trees.

"There's a lot of investment going into projects that will probably never return any kind of investment," said Aniruddha Sharma, co-founder and CEO of Carbon Clean, a startup that is capturing CO2 at industrial plants.

That's why several startups are targeting industrial emissions sources like steel mills and cement factories, where CO2 can be found at far higher concentrations than it exists in the atmosphere. The emissions are redirected from the factory smokestacks, and the CO2 is used to create products that either trap the gas forever or give it a second life—an approach known as carbon capture and utilization.

London-based Carbon Clean recently joined forces with Liquid Wind, a Swedish startup working on renewable liquid fuel. After Carbon Clean's scrubbers have captured CO2 from an industrial chimney, Liquid Wind combines it with hydrogen to create methanol.

Because it captures CO2 at the point where emissions are more plentiful, Carbon Clean aims to collect the gas for less than $30 per metric ton. That's a bargain compared to the several hundred dollars per ton that other direct-air carbon capture methods cost. For its methanol to compete with traditional fuel, Liquid Wind founder and CEO Claes Fredriksson thinks that costs will have to fall to between $20 and $30 per ton of captured CO2.

The joint venture aims to provide methanol fuel to the shipping industry within three years. Shipping giant Maersk has committed to making ships that are powered by methanol and expects them to be in the water by 2023 and is in discussions with Liquid Wind to provide the fuel.

Carbon Clean raised $22.7 million last summer, according to PitchBook data, and is backed by Chevron and Equinor Technology Ventures. Liquid Wind has received funding from from Siemens Energy, Uniper and its partner, Carbon Clean.

Turning factory CO2 into a valuable product could make such projects viable in developing countries where hefty government subsidies aren't an option.

"I don't think that the subsidies are essential," said 1955 Capital's Chung, who was a general partner at Khosla Ventures before starting his own firm.

The challenge for startups, once they have a scientifically proven method, is to find industrial partners who are eager to reduce their emissions and can help to develop pilot facilities next to their factories.

While at Khosla, Chung invested in LanzaTech, which is using CO2 emissions to produce goods ranging from fragrances to jet fuel.

Another startup, Blue Planet, has figured out a way to make rocks out of thin air.

Blue Planet's system runs air from smokestacks with high concentrations of carbon dioxide through a liquid solution that causes it to form a synthetic limestone, which can replace mined sand and gravel in concrete. The process can reduce or eliminate the carbon impact of concrete, which is a leading source of greenhouse gas.

"It doesn't sound too sexy but it's a really big market," said Brent Constantz, CEO of Blue Planet.

Last September, Blue Planet announced a $10 million raise and has been backed by Chevron, Leonardo DiCaprio and For Good Ventures. Its synthetic rocks have been used in concrete at San Francisco International Airport.

The startup is Constantz's second serious crack at carbon capture. In 2007, he founded Calera, which took a different approach to capturing carbon in cement. That company raised $182 million dollars from investors including Vinod Khosla and Madrone Capital Partners. Constantz stepped down as CEO of Calera in 2010.

He thinks the approach that Blue Planet is using will be more economically viable. Because the Bay Area company doesn't need to purify the CO2 in order to turn it into a carbonate form, the startup can sequester emissions using less energy than methods that turn CO2 into its pure liquid state. The synthetic rocks also cost less to transport since they are produced near places where people already live, rather than being mined elsewhere.

Point-of-emissions capture systems will be helpful in neutralizing future emissions, but they can't remove the hundreds of gigatons of CO2 in the atmosphere that scientists say will be necessary to arrest global warming. To do so will require a level of investment that could extend into the trillions of dollars, Constantz said.

"This is way too big for Silicon Valley or the classic idea that you will develop something in a garage," he added.

Comments:

Thanks for commenting

Our team will review your remarks prior to publishing.

Please check back soon to see them live.